Connie Mississippi: Circle of Time

May 4 – July 21, 2018

Connie Mississippi is known for the powerful and graceful turned-wood sculptures that position her among the important artists who have emerged through the contemporary wood-turning movement. Opening this spring in the Gerry Lenfest Gallery, this exhibition is an unusual form of retrospective, bringing together for the first time examples of her notable turned-wood sculptures, along with paintings, newer sculptures and original artist books that illuminate her more well-known work. Together these works make a larger whole, unified by the artist’s longstanding interests in dreams, nature, and spirituality.

Major support for Connie Mississippi: Circle of Time is provided by the O’Boyle Family.

The exhibition program and documentation is generously supported by the Fleur Bresler Publication Fund and the Cambium Giving Society of The Center for Art in Wood, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, Philadelphia Cultural Fund, and the Windgate Charitable Foundation. Corporate support is provided by American Kitchen Machinery, Inc., Boomerang, Inc., Penn State Industries and Signarama Center City.

- Essay - Albert LeCoff, CoFounder and Executive Director Emeritus, The Center for Art in Wood

- Essay -Miriam Seidel, Guest Curator

- An interview with Connie Mississippi, By Miriam Seidel

- Essay-Glenn Adamson, Senior Scholar, Yale Center for British Art

- Video

CONNIE MISSISSIPPI: INSPIRING PLACES AND WORKS

CONNIE MISSISSIPPI: INSPIRING PLACES AND WORKSBY ALBERT LECOFF, CO-FOUNDER, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR EMERITUS

THE CENTER FOR ART IN WOOD

Connie Mississippi’s cerebral and physical journeys have long informed and inspired her wide and engaging exploration of media and message. Inspirations came to her as a constant reader, writer and traveler, and she had only to find the media and methods to make her imaginings come true. By the time we met in 1990, she was focusing on wood. She already had honed skills in painting, embroidery and sewing, writing and ceramics, and had often participated in group exhibitions and discussions as well as international travel.

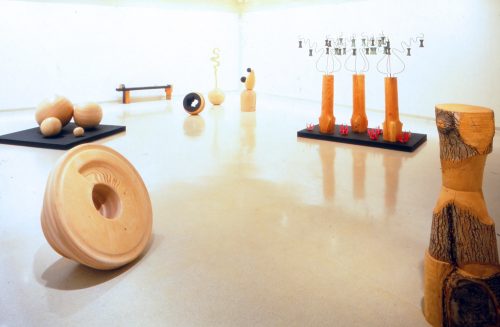

Garden of Time exhibition held in 1999 at the Brand Library and Galleries, Glendale, California

Every place she lived and everything she read informed Connie’s art and her eventual foray into wood. Born deep in the American South, she grew to love nature and discovered her talents in art before she graduated from Memphis College of Art and earned an MFA from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

In New York City, she discovered museums, galleries, and working artists. In Los Angeles, she discovered a way to shape large wood sculptures that she described on January 22, 2013:

“I discovered the lathe and its possibilities. Seeing the characteristics of the works produced on the lathe with their vertical axis and symmetrical forms, I realized there was an entire world of exploration to be done within these structural parameters.”

Connie’s designs are as large as her ideas. After a year working with a lathe artist to learn turning techniques most of the available wood and lathes were too small to work at the scale she wanted. Her solution was to acquire a custom lathe, and to glue up pieces of Baltic birch plywood into large stable masses, a technique inspired by Rude Osolnik. On the lathe, Connie could turn sculptures up to 10 feet long and 44 inches in diameter. With assistants to help maneuver such large works, off that lathe came totems, trees of life, The Black Hole (1992) and Sea Chamber (1996). So did Pythagoras—a pair in the exhibition that the Center owns—a prototype turned and carved out of a log, then cast in bronze for a garden.

So—This is how contemporary wood turning found Connie:

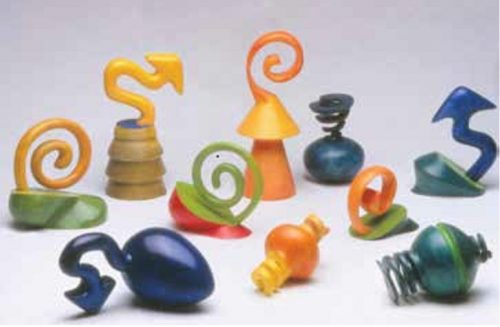

Connie responded to the Center’s 1997 Curators’ Focus: Turning in Context call for work. She submitted ten pieces from a series called Time Line—Ten Objects. Her photographs and artist’s statement for the exhibit immediately distinguished her from all the other entries:

“Time Line—Ten Objects” is a work in progress. Each of these pieces represents one year of the 20th Century. The entire work will be comprised of 100 small sculptures, none larger than 12 inches. Each piece is accompanied by a notation of important events that occurred during the represented year. Choosing to make a sculpture for each year of this century was a deliberate act of homage and discipline. Those years are what formed us as individuals and as a culture.

In 1998, answering a survey in connection with Wood Turning in North America Since 1930, Connie recalled:

In 1991 at the Challenge IV exhibition in Philadelphia, lmet Todd Hoyer and Albert LeCoff. They were both very supportive of what l was doing. That gave me a tremendous boost since l knew virtually no one in the wood turning world and had no way of knowing, other than my own instincts, that l was onto something.

Years later, she wrote:

Continuing with this scale, l produced many more of these small pieces which l chose to paint in various colors and some were displayed in open wooden boxes.

In New Mexico, Connie pursued several new bodies of work, including in wood, paint and watercolor. The carved and finished Landscape series evolved to capture how the deserts merged with the mountains. The Kabbalah paintings evolved after seven years of study. They were abstracted from the concept of the Four Worlds, which are the invisible physical, psychological, spiritual and divine realms of the universe. New Mexico’s landscape of undulating planes is seen in the background of many of the paintings. Variations of the X symbol represent angels, a form that also appeared in wood. Also, in this exhibition are Dream Journals which came about through a study of her dreams in a dream group, then her physical interpretations of that study by way of watercolor paintings of the dreams.

Time Line – Ten Objects | 1996 | Basswood, turned, carved & painted | 8 x 4 x 4 in. each | Photo by John Carlano

Now in California, Connie’s work includes small black and white sculptures which reflect changes to her energy and wear and tear on her body through her circle of time. With Connie’s art featured at the Center, our friendship and comradery comes full circle. We thank Miriam Seidel, Guest Curator, for her extensive research, interview and essay about Connie‘s work, and Glenn Adamson, whose insights reinforce Connie’s organic thoughts and instincts. It is my pleasure, however, to muse over Connie’s standout role within the wood art field and the wisdom and stories and strengths she brings.

PHOTO BY HANNAH GREENSTEIN

CONNIE MISSISSIPPI’S

CIRCLES OF TIME, SPACE AND SPIRIT

BY MIRIAM SEIDEL, GUEST CURATOR

Connie Mississippi is known for the powerful and graceful turned-wood sculptures that position her among the important artists who have emerged through the contemporary wood—turning movement. But her work has always been informed by deep streams of spiritual inquiry, giving a ballast of meaning to her abstract and semi-abstract forms. Like Robyn Horn, another significant artist of her generation, Mississippi began as a painter, and she has continued to paint, making images that embody more explicit forms and symbolism.

This exhibit, Connie Mississippi: Circle of Time, is an unusual form of retrospective, bringing together for the first time examples of her notable turned—wood sculptures, along with paintings, newer sculptures and original artist books that illuminate her more well-known work. Together these works make a larger whole, unified by the artist’s longstanding interests in dreams, nature, and spirituality.

Mississippi undertook a seven-year study of Kabbalah, the mystical tradition of Judaism, while she was living outside Santa Fe, New Mexico. Having left her Episcopalian tradition behind, she found the concepts of Kabbalah satisfied a desire for spiritual exploration. The Kabbalah is a compendium of ancient and medieval tenets and practices, with an emphasis on direct individual experience of the Divine. Long a semi—secret tradition, it has recently become more openly available for study by Jews and non—Jews. its combination of extremely abstract concepts and potently dense visual diagrams makes it particularly attractive, I believe, to visual artists.

Meanwhile, Mississippi’s work had long been enriched by an interest in other religious traditions. While a student at Pratt, Mississippi did her senior thesis on the iconography of the Hindu mandala. Later travels in Mexico familiarized her with Mayan and Aztec myths and artwork, and in New Mexico she sought out Native American ceremonies and imagery. Many of these elements found their way into the elaborate visual records of her Dream Journals, two of which are included in this show.

Kabbalah Book 1 | 2008 | p. 5 | Watercolor, gouache, acrylic and handmade paper | 15 ½ x 11 in. | Collection of the Artist

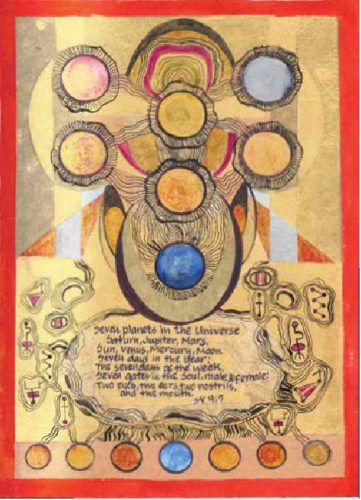

Also included here are two Kabbalah Books she created, each painted page distilling concepts and images from her studies. (Mississippi now teaches Kabbalah to others.) We see here versions of the Tree of Life—a representation of the ten Sephirot (attributes or emanations) of the Divine; of Jacob’s Ladder; magic squares (a kind of numerical puzzle); and images illustrating the hidden meanings of numbers and the letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

Mississippi’s series of semi-abstract, Kabbalah-influenced paintings, The Four Worlds, shows how she has developed her own symbol system, integrating concepts from Kabbalah with imagery reflecting her powerful experiences of nature, especially while living in the monumental landscape of New Mexico. Each painting is divided into four ascending layers, moving up from the lowest of the Kabbalistic tiers of existence, the physical, through the psychological, the spiritual and finally the Divine at the top.

The imagery of each tier often seems to resolve into layers of landscape as we commonly experience it, with earth at the lower levels, and horizon and sky moving upward. Yet, separated as they are, each layer maintains its integrity. When an image repeats in several tiers, it suggests how something may be perceived differently through each different lens of experience.

We see here the elongated, curving X-shapes, winged forms that Mississippi identifies as angels. A repeating cross-hatched form is one she connects with Indra’s Net—a Hindu/Buddhist story that visualizes the interdependence of the universe as a network of mutually reflecting nodes of energy; she has found it to resonate strongly with her understanding of the Kabbalah. These are combined with mountains and rivers, and an abstracted cloud form—all reflecting her sense of the spirit’s immanence in the land, which she discusses in more detail in the interview that follows.

To return to the artist’s sculptures, viewing them in the light of this less-seen facet of her work, is to understand them in a new way. The undulating forms of her Circle of Time series are inspired by the mountains she could see from her New Mexico home; their circular shapes seem to suggest a unity that transcends linear time, closer to the direct felt experience of the higher worlds in Kabbalah.

The repeated, elegant totemic shapes of her monumental Pythagoras sculpture (in both wood and bronze), and the strong spiraling forms of her tour-de-force turned sculptures such as Sea Chamber and The Black Hole, show her sense that geometry can also be a portal to representing higher truths. It’s worth noting the historical links between Pythagoras and Kabbalah. The numeric formulas espoused by Pythagoras, a part of his larger mystic cosmology, influenced Plato and his followers, and Neoplatonism is recognized in turn as one source of Kabbalistic tradition. Connections like this spiral and ripple through Mississippi’s work, beckoning us with mysterious accretions of meaning.

CONNIE MISSISSIPPI STANDS IN HER 1999 GARDEN OF TIME EXHIBITION HELD AT THE BRAND LIBRARY AND GALLERIES, GLENDALE, CALIFORNIA

How did you come to study Kabbalah?

I was finding that I needed a religious practice in my life. And I wanted a much broader approach to the divine. I had read about Kabbalah, and a friend of mine in Santa Fe told me that there was a Kabbalah class at a temple there. And I studied there for seven years. My teacher used primarily the works of a teacher called Z’ev ben Shimon Halevi, an Englishman who’s written many books on Kabbalah.

And at some point you started using it in your artwork?

Yes. I sometimes need to do a painting that references Kabbalah, sometimes really abstractly, but I find it a source of inspiration. I’m looking for a visual form for the idea. And the Tree of Life is a great place to start.

What about your series, The Four Worlds?

The Four Worlds is another idea from Kabbalah. The bottom is the physical world; above that is the psychological world; above that is the spiritual world, and above that is the divine world. And in meditation you work your way up the tree in those different worlds.

Do you have a meditation practice that’s related to

this too?

I have a yoga practice. But my meditation is the work. I can go into an absolute… I don’t want to get too esoteric.

No, but what I’m hearing is your artwork is your meditation. You’ve also got these very compact symbols that appear in these paintings.

The elongated X’s—those are symbols for angels. Angels figure in very largely in the Kabbalah. The belief is that God sends down angels for specific projects, and then when they’re finished, they go back up into the Divine. I like that idea that we all have angels to help us either in adversity or success, or whatever. I don’t mean to be too literal—you can use it however you want.

Could we say that in your paintings, you’re calling on the angels?

Well, I wouldn’t say calling on the angels. I just think they’re there.

You’re just making them visible.

Yes, I’m attempting to make them visible.

In the long painting, Jacob’s Ladder, you have some really interesting swirly forms inside.

All of that is about energy. In Jacob’s Ladder, the earth is at the bottom and the Divine is at the top. And Jacob saw in a dream angels going up and down a ladder. And that’s the angels going up and down the ladder.

What about the painting called Soft Presence?

You see the elliptical shape at the top? When I was living in New Mexico, there was an Indian reservation out behind our ranch, and it was this vast open space, and then further out was a mountain range. And almost every afternoon, this gigantic cloud shaped like that sideways ellipse would appear, but it would appear in different sizes and in different colors. And that to me was a sign of the Divine, for sure. So that’s where that symbol originated.

Oh, it’s a cloud!

It’s a cloud, but it’s more than a cloud.

So these paintings are inspired by these landscape experiences you’ve had.

Exactly. Just like Circle of Time is. The Circle of Time pieces make reference to the mountains, and they also make reference to the sand dunes that occur in the desert with the wind.

Was it hard to leave that landscape?

It was and it wasn’t. It was a very harsh landscape to live in, between the heat and the cold and wind. But the thing I miss most about the Southwest is the people. You live in the midst of everyone. Native American, Hispanic, and they all have their own unique approach to reality and to the Divine. That dream painting with me looking in the mirror at that Native American dancing? That kind of thing was the norm, to see those dances, people walking around in those costumes.

Where does time come into the Kabbalah? Is it like a “circle of time,” with time coming back around in a way?

Time does come back around, don’t you think? Out there in the desert you feel time in a different way from anywhere that I’ve ever experienced it. The present and the past are interconnected. The future even.

Can you talk about the painting called Blue Field?

This one is different in that the sky is the ground, so the landscape floats. And that is very much what can happen in the desert. You’re looking—when they talk about mirages, there really are mirages. All of a sudden, the landscape will just rise up off the desert floor, and there’s this whole world going on, suspended. But again, here’s the mountains and the angels and that cloud that persists in all of them.

I see that the Southwestern landscape is so much a presence here.

I think the landscape can speak, not just in the Southwest. I’m looking out right now at these gorgeous, inspiring Santa Ynez mountains outside my home.

LIKE SANDS THROUGH THE HOURGLASS:

LIKE SANDS THROUGH THE HOURGLASS:CONNIE MISSISSIPPI’S SCULPTURAL FORMS

BY GLENN ADAMSON, SENIOR SCHOLAR, YALE CENTER FOR BRITISH ART

At the end of his life, the art historian Michael Baxandall wrote a short book about memory. It opened with a passage about sand dunes, desert forms carved by the winds. You can probably picture one in your mind’s eye: a sharply defined carve-out on the leeward side, and a gentle slope on the windward. Baxandall noted the way that lighter and heavier particles in a dune re-arranged themselves constantly in response to the winds, and also the way that each dune is shaped in response to the others around it: “in this structure is deposited an internalized selective record of its own history.”1 Baxandall saw in this natural phenomenon a metaphor for human memory. Past experiences constantly shift within a social setting, sometimes sinking to the bottom only to rise again; and each person’s memory is subtly shaped by the influence of others, in ways that may be quite difficult to grasp.

Baxandall’s text comes to mind in relation to Connie Mississippi’s series Circle of Time, whose shapes so strongly recall windswept landscapes. It was not a surprise to learn that they had been inspired by her move to Santa Fe in 2001, to a location overlooking a pueblo. After years living in the urban setting of Los Angeles, this new environment had a profound impact on her: the hugeness of sky, “so colorful and so omnipresent;” the undulating rhythms of the desert, its sands shifting moment to moment, within formations created over eons. 2 In the sculptures, she compresses these effects into the dimensions of a handmade object. The forms are indeed geological, but also abstract; they could be taken as depictions of temporality itself.

The pieces in the Circle of Time series are also colorful, rendered in an unusually bold palette—“not the colors you usually see in sculpture,” as Mississippi points out. Most are made of high-grade Baltic birch plywood, which has a kind of neutrality about it. Absent any ingrained figure or

dimensional limitation, plywood is steadfastly utilitarian—Mississippi compares it to the everyday materials used by the Italian Arte Povera movement. Its main visual quality is its layered structure, which beautifully articulates the curves of Mississippi’s forms, suggestive of a geological stratigraphy. One piece from the series, Dream Landscape 1,is embellished with a brightly painted scene of snakes and sand. The images originated in the artist’s unconscious, and were recorded in dream journals she was keeping at the time. Another, entitled Sunset Striations, is made from a special plywood of Chinese manufacture that already has color dyed into the various layers. It’s as if she had carved into a rainbow.

Laminated plywood has been Mississippi’s preferred material since she established herself in the field of wood art; she chose it in order to emphasize form and concept, rather than the natural qualities of timber that interest so many other wood turners. Two of her most significant early works, The Black Hole and Sea Chamber, exemplify the austerity and power of her formative years. They are large in scale, over three feet across. Both play on the idea of the hollow vessel, and imaginatively connect that common format to very unexpected referents out in the world: one in deep space, the other in the deep sea. Both can be interpreted as statements about temporality. In an astronomical black hole, the very stuff of the universe is cyclically generated and destroyed. The asymmetrical Sea Chamber presents itself as a more mythical source-object, perhaps the source of dreams rather than anything solid.

Given Mississippi’s interest in the deep cycles of time, the year 2000 was inevitably an important moment for her. She decided to commemorate the event by making a physical depiction of the 100 years of the century just past. The vocabulary of spirals and arrows does suggest a timeline, like one seen at the back of a history book, but also the dynamic forms of that other great Italian avant garde movement, the Futurists. When I first saw these

small works, somewhat reminiscent of the abstract “hand sculptures” made at the Bauhaus, I assumed that she had designed each one with a specific year in mind. Not so. She made the works first, and allocated the chronology only after the fact. This inversion of the expected seems to me very revealing about Mississippi’s working method; there is absolutely nothing didactic or linear about her approach. She prizes instinct.

Mississippi has used industrial-scale equipment to fashion her work for a long time—in Los Angeles she had a custom-made lathe with a 10-foot-long bed and a 44-inch swing. But even when using an auto body grinder, she works in an exploratory manner, using the lathe and other tools as form generators, letting the form happen rather than dictating it in advance. The monumental work Pythagoras is an impressive instance of this method.

Though it towers 8 ½ feet high, the composition is still intuitive, as is the theme of the work; its title suggests a relationship to mathematical theorems, but there is nothing rigidly geometrical in the shapes. It was conceived for the collector Bruce Kaiser, who wanted to place the work outside. So Mississippi had it cast in bronze. Sometime later, the wood original split open due to the natural movement of the timber. She accepted this “checking” as an organic part of the work’s life-cycle. Comparing the wood version, with its vertical rifts, to the seamless bronze is like witnessing two moments in the object’s history side-by-side.

The final sculptural work of Mississippi’s in the present show, Archangel, is the one that relates most closely to her painted imagery. As Miriam Seidel explains in her curatorial essay, these works in acrylic are based on the artist’s close study of the kabbalah, and development of a private symbolic repertoire based on that belief system. Many of her paintings feature ‘X’ forms that are meant to represent angels. The wooden sculpture replicates this shape; the plywood is stacked front to back, and was carved into a rippling, topographical surface before being painted black. One can imagine it as eroded into its present form by a strong wind, over many years.

I suppose if guiding spirits are watching over us, they might indeed look something like this: tracing the ups and down, the hills and valleys, of experience. Connie Mississippi’s art is an art of contrasts: industrial material that seems to breathe with organic life; still objects that speak of time; images of potent clarity that are also tactile. It’s rich, and it’s complicated. Just like the days of our lives.

FOOTNOTES

1 | Michael Baxandall, Episodes: A Memory Book (London: Frances Lincoln, 2010), p. 20.

2 | Quotations from Connie Mississippi are taken from an interview conducted on 20 February, 2018.