Listening Room

Conversations in craft continue in the Wood Shed

CERF+ on Opportunities for Artists During COVID-19

Recorded April 6, 2020

A grassroots organization founded “by artists for artists” in 1985, CERF+ supports craft artists and makers who have lost resources or revenue due to disaster—from hurricanes, tornadoes, and floods to terminal disease, studio fires, and global pandemics. In this short conversation, Cornelia Carey, Executive Director of CERF+, describes the organization’s work to the Center’s Artistic Director, Jennifer-Navva Milliken, and shares ways to help craft makers, whose livelihoods and practices are more vulnerable than ever in the time of COVID-19.

Object Lesson: Albert LeCoff on Jean-François Escoulen’s wacky, crooked turnings

I first met Jean-François in 1995 at a French wood turning conference staged in a traditional French village. The entire village provided accommodations and meals for this venture, attended by over a hundred people, mostly from France and Germany. I was a presenter and Jean-François was demonstrating. My wife Tina brought him to my attention after watching him turn a traditional European trembleur. Escoulen turned this six-foot long, one-piece, delicately thin sculpture thinner and thinner, while another person steadied the long end as it extended off the lathe. In Europe, fragile trembleurs are protected in tall glass cylinders. Escoulen’s demonstration showcased his training and skills, gained during his formal apprenticeship from age 16–23 with his father, a master spindle turner, in his father’s home shop. In the same conference session, Jean-François featured a fifteen-year old student, Remi Verchot, who also expertly executed his trembleur. This offered a premonition of what a good teacher Jean-François would become.

Instantly, I realized that Jean-François would be a good European candidate for the Center’s newly established International Turning Exchange (ITE). The Wood Turning Center created the ITE residency in 1995 as a collegial experience during which the seasoned fellows could research and explore new work for two months, away from the distractions of jobs and making a living. The ITE typically awards eight fellowships to an international pool of applicants. In 2020, its 25th year, the ITE generally includes five artists, a visual documentarian, a scholar/educator/writer, and a student artist.

Jean-François knew of the Center for Art in Wood and that’s how I got invited to present at the conference. Though I was not fluent in French, nor he in English, I was determined to convince him of the ITE opportunity. Tina and I followed him home to his village, a three-hour drive through picturesque, rural France. He provided a translator so I could explain ITE to him, and the unique experience I believed it would be for him and his fellow turners. He applied and was accepted into the 1996 ITE, which started a run of talented French and European turners participating in the ITE residency.

Jean-François’s practice is important because he epitomizes the French way of learning classical turning, and then evolving one’s practice into one’s own. When he started turning, teens in France were allowed to pursue a trade rather than finish high school; in his teens, Jean-François became a dedicated turner. His career reflects how Europeans learn and perfect ornamental turning on complex machines, that they learn their skills through structured apprenticeships and are certified by France in official proficiency tests.

Soon after his apprenticeship, Jean-François diverged from classic European approaches, and developed his own complex artistic forms, based on his classic training. His pre-ITE pieces incorporated lidded boxes, classical elements, and spindles, but he manipulated each so that the spindles bent and contorted sideways, springing out of the lidded boxes. Through this masterful “dis-orientation,” utilizing a chuck he invented, he created tension and balance at the same time. Among his inspirations, he notes artists Picasso, Salvador Dalì, and Hieronymus Bosch. His understated bases also stabilize the work, and each piece is executed with the finest technical craftsmanship. In 1982, France honored Jean-François with the Meiller Ouvrier de France, which is the highest award a French artist can receive.

By 1996 when Jean-François attended ITE, he was pursuing his desire to become an artist rather than a production spindle turner. The whimsical, off-center, lidded boxes for which he was so known in France became a hallmark during his ITE summer in Philadelphia. During his two months, he made fast friendships despite the language barrier, and gunned ahead in his visions of art he could execute in wood. Through his new body of work, his creativity, and his sense of humor emerged. He explored making critters and creatures for the first time and he broke out of brown natural wood finishes into playful colors. Genuinely collegial and focused, upon his return to France, Jean-François embarked on forming the French turners ’network, AFTAB, and created the Escoulen School of Woodturning, drafting teachers from around the world to share their unique approaches.

Breakthrough from boxes to critters during ITE

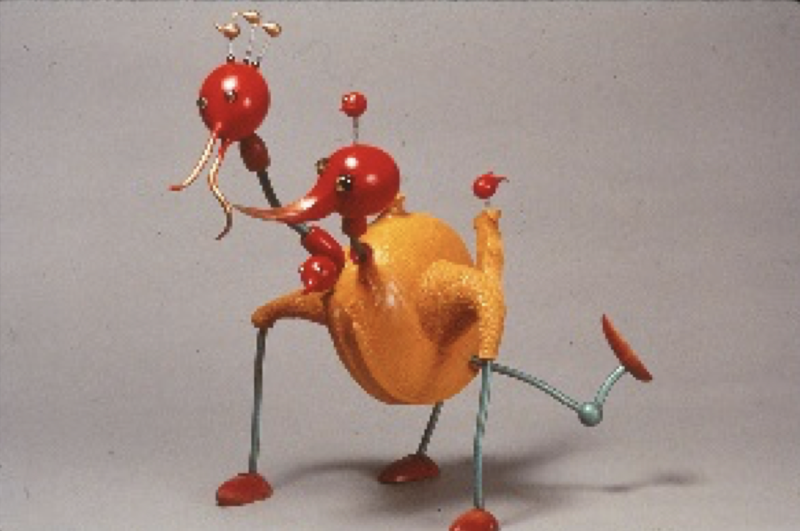

Escoulen’s breakthrough at ITE was his explosion into animal creatures, the first being La Metamorphose, OBJ 301. The hollow body is a turned and hollowed out burl. The framework, head, legs, and tail are clearly turned. He pursued humorous critters for the remainder of ITE.

Darling, You Are Getting Better Looking Every Day, OBJ 572 is also an ITE exploration. He used turned components (head, body, legs), but reoriented them and assembled them to create humor, tension, and fragility. This piece could be an accident waiting to happen! Darling…, comically expressed Jean-François missing his family and being attracted to his fellow residents.

Through the initial weeks of ITE, Jean-François and his fellow ITEers utilized largely natural wood finishes. Close to the end of the ITE summer, the residents attended the Emma Lake International Collaboration in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in Canada. There, surrounded by other international artists, the ITE group decided that their works could use some color. At Emma Lake, Jean-François collaborated with Mark Sfirri to create Hurdy-Gurdy, OBJ 302 as his first experiment in combining turning, texturing, and paint.

Back at ITE, Jean-François and his fellow artists continued to explore color in their work. One morning, Terry Martin from Australia overheard Jean-François making the “Buck, Buck, Buck” sound that chickens make as the Frenchman was turning on the lathe. Acknowledging Jean-François’ limited English, Terry and Jean-François laughed and realized that the language of chickens is universally recognized. So, with their mutual sense of humor, they started speaking Buck, Buck, Buck to each other.

One of Jean-François’s last ITE experiments became The Chicken Family goes on Vacation, a reminder of the ITE trip to Emma Lake and the chickens he raised at home. This multi-headed critter has one head for each of his fellow ITE artists.

Neil and Susan Kaye of Wilmington, DE, were enthusiastic followers of the ITE program. They often hosted the ITE Fellows to show their collection, and serve crab legs, beer, and ice cream from their home ice cream bar. The Kayes donated Darling…, along with other works, to the Center’s permanent collection.

1996 ITE Fellows feast at the Kayes. Left to right: Terry Martin, Michael Brolly, Hugh McKay, Jean-François Escoulen, Neil Kay, Susan Kaye, and Susan’s sister Sally Donnelly (Strano)

Support Your Favorite Programming at the Museum

The Museum for Art in Wood is able to provide an impressive array of programs and services thanks to support from our patrons. Please consider making a donation to help us continue these great conversations in craft.