If one travels to Cairo in search of mashrabiyat, the neighborhood of Islamic Cairo presents a number of picturesque specimens. Al-Muizz Street, founded by the Fatimid Caliph, al-Muizz li-Din Allah (341–365 AH / 953–975 CE), is a 1km street that connects the gates on either side of the neighborhood—Bab al Futuh in the north, to Bab Zuwayla in the south. The street was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979, due to the density of historic buildings and locations along the route, which date from the early Fatimid caliphs to the reign of Mohammad Ali (tenth–twentieth centuries CE). Among them are the famous Khan el-Khalili souq, the Qalawun complex of Mamluk architecture, the legendary el-Gamaliyya Street, and Bayt al-Suheymi.

Bayt al-Suheymi is one of the best preserved Ottoman-era (1517–1867 CE) structures in Cairo today. It was inhabited until 1931 CE, when the al-Suheymi family sold it to King Fouad’s government for 6,000 Egyptian Pounds. It was neglected following the devastating earthquake of 1992, but underwent extensive restoration in 2000 and now it is maintained by the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

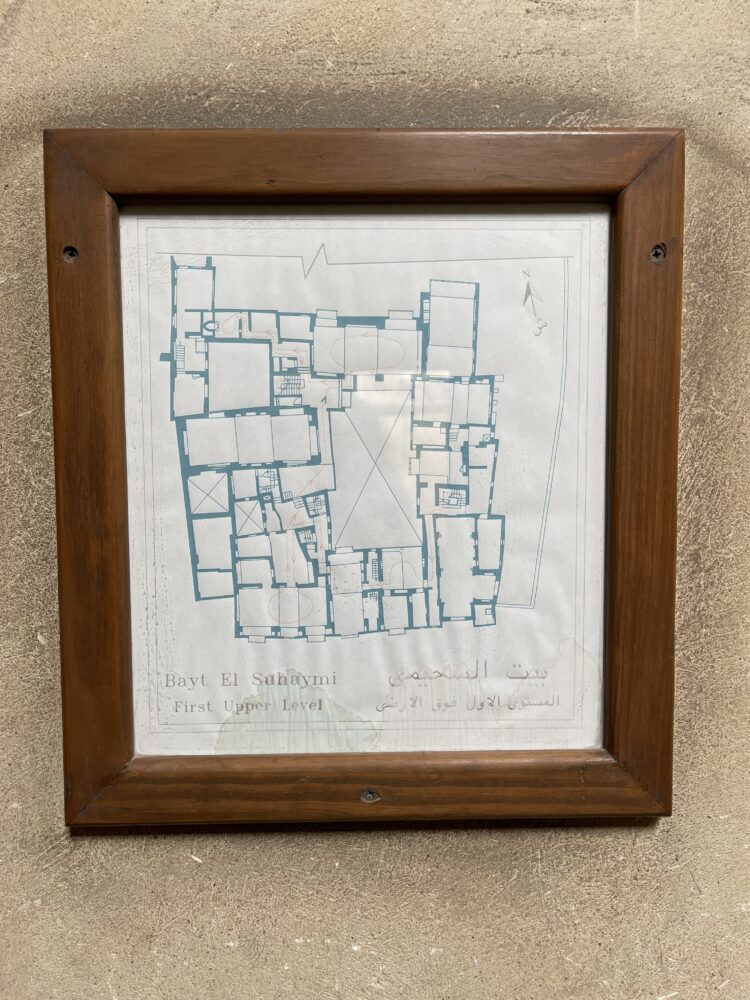

The house follows a typical Ottoman plan: a “dog-leg” (angled, to block direct views) passageway from the street leads to the large but private sahn, or courtyard. The wings of the house are wrapped around the courtyard and they include salamlik—public salon spaces for hosting gatherings, from which women were generally excluded—and haramlik—private quarters that housed family life, principally women, children, and domestic help.

Though uninhabited for almost a century, Bayt al-Suheymi does feature traces of furnishings that give a sense of Ottoman interiors. The wood-turned mashrabiya latticework is incorporated in the chairs, tables, and wardrobe closets throughout the house, along with stunning handwoven carpets protecting the marble floors. Mamluk and Ottoman structures are feature 360-degree ornamentation—the visitor who looks up will be rewarded by incredible ceilings featuring highly detailed carvings with painted embellishments. Cedar for these installations was imported from Syria; the Nile Delta region, while fertile and a source of agriculture for millennia, is not a habitat that supports forests.

This brings me back to the mashrabiya. In a previous post, I mentioned that they are generally made from zan, or beech wood. The zan is a slender tree that is imported to Egypt from Romania or Sweden; its hard and fibrous composition is suited to the needs of the mashrabiya segments, which need to expand and contract in the harsh sun and cool nights in order to perform their function over centuries. The mashrabiya windows in Bayt al-Suheymi fill every window, at every scale—whether overlooking the busy street, or facing the serene and private sahn.

Bayt el-Suheymi is really comprised of two houses, built at different times by different families. This was a common practice among wealthy homeowners, and often buildings—as is the case with Bayt al-Kritliyya (now the Gayer-Anderson Museum)—often span political and architectural movements. The first resident was Sheikh Abdel Wahab el Tablawy, who built the sahn and southern building in 1648. A second occupant, Ismail bin Shalaby, built the northern section during his residence in 1796. The home gets its name from the Sheikh Ahmed as-Suheymi, the final inhabitant, who was the sheikh of the nearby al-Azhar mosque—another Ottoman architectural treasure in the neighborhood.

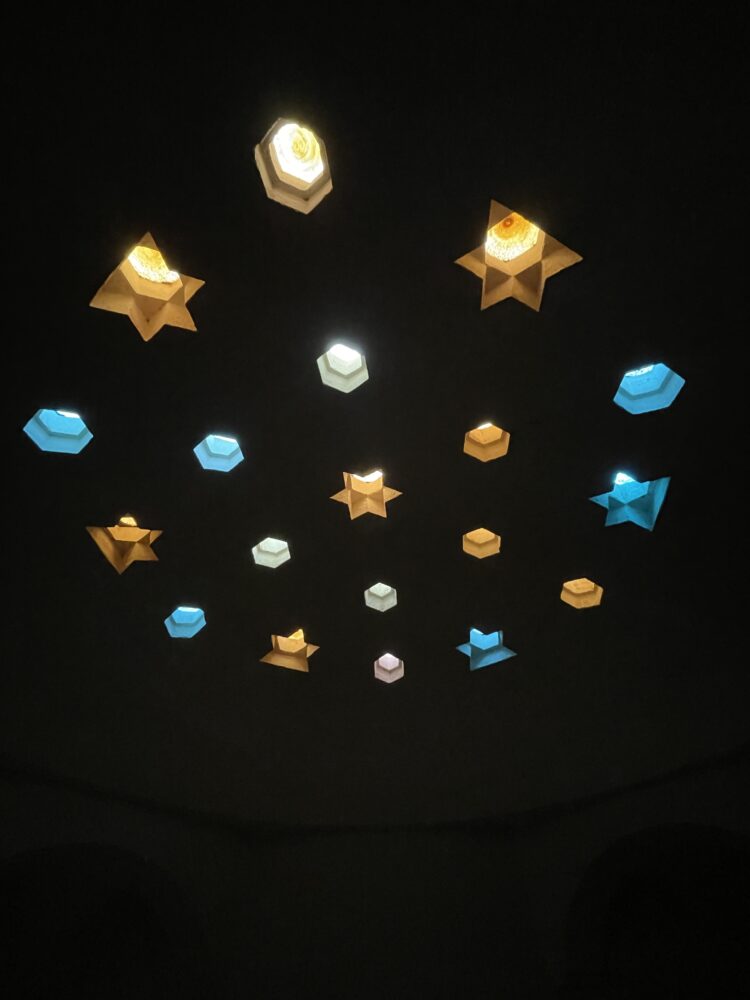

The residence has some 30 rooms within its three stories, and multiple stairways leading to various suites. If you’re lucky you can find the hammam, or bath—a beautiful space with a domed ceiling and embedded colored glass that gives it an ethereal glow.

For a virtual 3-D tour of Bayt el-Suhaymi photographed by Ahmed Attia, click here:

http://www.3dmekanlar.com/en/bayt-al-suhaymi.html