Mashrafiya or mashrabiya?

المشرفية أو المشربية?

Mashrabiya or mashrafiya?

While this object is generally referred to across the Maghreb region (North Africa) as mashrabiya, the word raises an interesting etymological question.

The word mashrabiya attests to the object’s multi-functionality: in Arabic, sharaba or شرب (root letters are ش, ر, ب) means “drink,” while sharafa or شرف (ش, ر, ف) translates to “see”. Whether the original word is mashrabiya or mashrafiya remains unclear; what we do know is that the form evolved over time to serve a number of purposes, including separating interior spaces according to gender and function; providing privacy and shade from the sun; and serving as a decorative element to otherwise austere building façades.

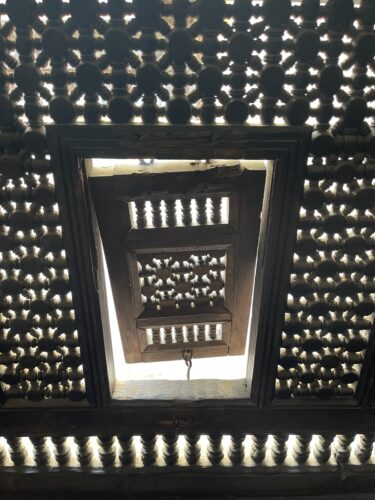

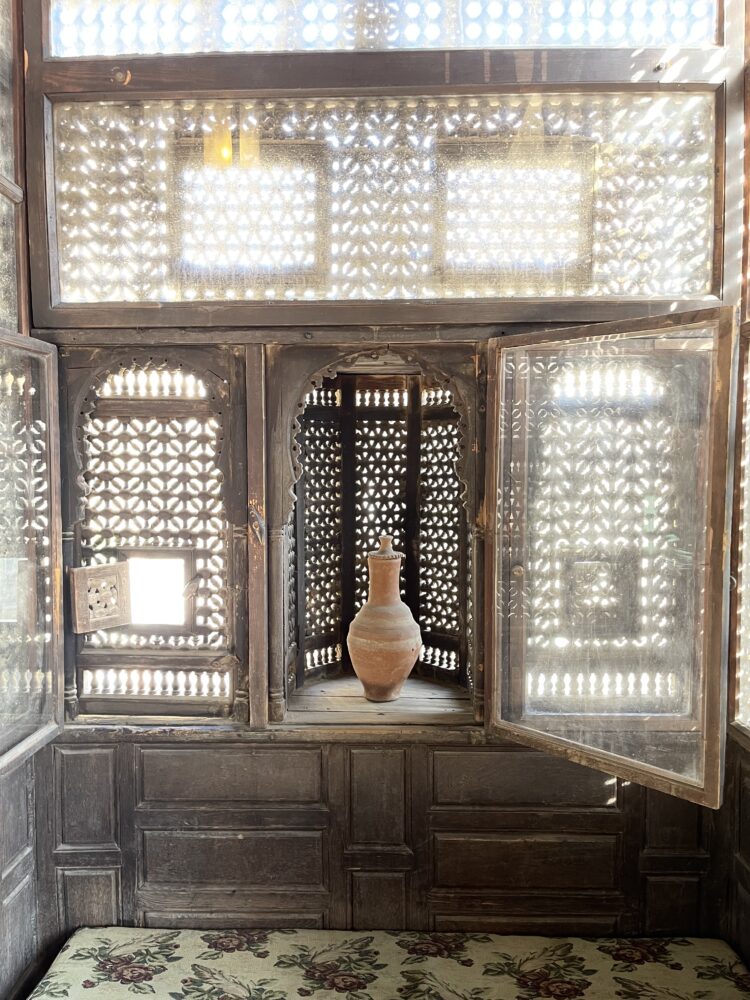

There are clear factors that indicate the purpose of a given screen. A mashrabiya will have a niche built into it that enables the placement of a ceramic jar, or ‘qulla (قلة), for holding cold water. As air from the outside passes by, it is cooled by the condensation from the jar, thus introducing passive cooling. A mashrafiya, on the other hand, will often be fitted with a small, hinged aperture that can be opened and shut. It might allow the sharing of objects (who hasn’t thrown their keys from their position on an upper floor to friends waiting on the street below?) or letters to be mailed.

Here we have a combination of mashrabiya and mashrafiya examples! Note the ‘qulla placed in the center niche!

Generally, the word mashrafiya is not recognized; introducing it into conversation will elicit blank stares. But on a recent visit to the Gayer-Anderson Museum in Islamic Cairo, a guide was careful to point out the differences between the mashrafiya and the mashrabiya, and to demand correct usage of the terms from his visitors. This was simple enough at the Museum, which is also known as Bayt al-Kritliyya in honor of an important and wealthy resident and owner, a woman from Crete (hence “al-Kritliyya”).

The house, which was built during the Mamluk period in 1040 AH (al hijri)/1631 CE and joined to the older neighboring house (b. 947 AH/1540 CE) some unknown years later, is plentiful in mashrabiya and mashrafiya structures throughout its interiors and exterior-facing windows. One of its most unique features is the array of wood-turned lattices—some of which feature decorative lettering embedded in the designs—on the rooftop, framing views of the nearby Mosque of Ibn Tulun. Fans of James Bond may find these views familiar—they served as the location for memorable scenes in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), along with the salamlik (salon, or reception/meeting room).

Stills from the infamous James Bond movie “The Spy Who Loved Me” (1977).

Roger Moore and assorted villains make use of mashrafiya to skulk about and commit devious acts.

Roger Moore in a pensive moment with the minaret of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun.

Bayt al-Kritliyya stands today as a result of efforts by the Committee for the Conservation of Arab Monuments, which saved it from demolition in the early twentieth century. In 1935, a British-Irish surgeon in the Royal Army, who had been seconded to the Egyptian Army, took up residence in the house and filled it with objects purchased during his travels throughout Asia. When he returned to the United Kingdom in 1942, he turned the house and its contents over to the Egyptian antiquities authority, and it remains one of the best preserved historic buildings in the city.

View of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun from the roof of Bayt al-Kritliyya. Established in 265 AH/878 CE by Abbasid ruler Ahmad Ibn Tulun, this mosque is one of the oldest mosques in the African continent.

This narrow balcony is lined with mashrafiya that provide a view to the salamlik below. It is the only interior space in this traditional residence that linked the women’s quarters, or haramlik, with the spaces of hospitality and gathering that were visited by men only.

Screen shots from The Spy Who Loved Me, United Artists, 1977

All other photos by Jennifer-Navva Milliken, 2022